Women’s rights, minority rights inseparable

VIDEO: Francelia Gleaves (now McKindra) not only was one of the first people to work at length on Title IX issues in the 1970s, she was one of the few African Americans doing this work. To her, minority rights and women’s rights were inseparable, though not everyone felt that way, she says in this 2015 interview.

A lot was happening on both fronts at that time. White America still was slow to adjust to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (which, by the way, failed to prohibit discrimination based on sex in some of its provisions, hence the need for Title IX). Martin Luther King had been shot dead before the 1968 presidential election. Rep. Shirley Chisholm was about to become the first African-American woman to run for president in 1972. The second wave of feminism was cresting. Lobbying for an Equal Rights Amendment to prohibit sex discrimination finally was bearing fruit. Progress for black women depended as much on stopping sex discrimination as on stopping racial discrimination, Gleaves believed.

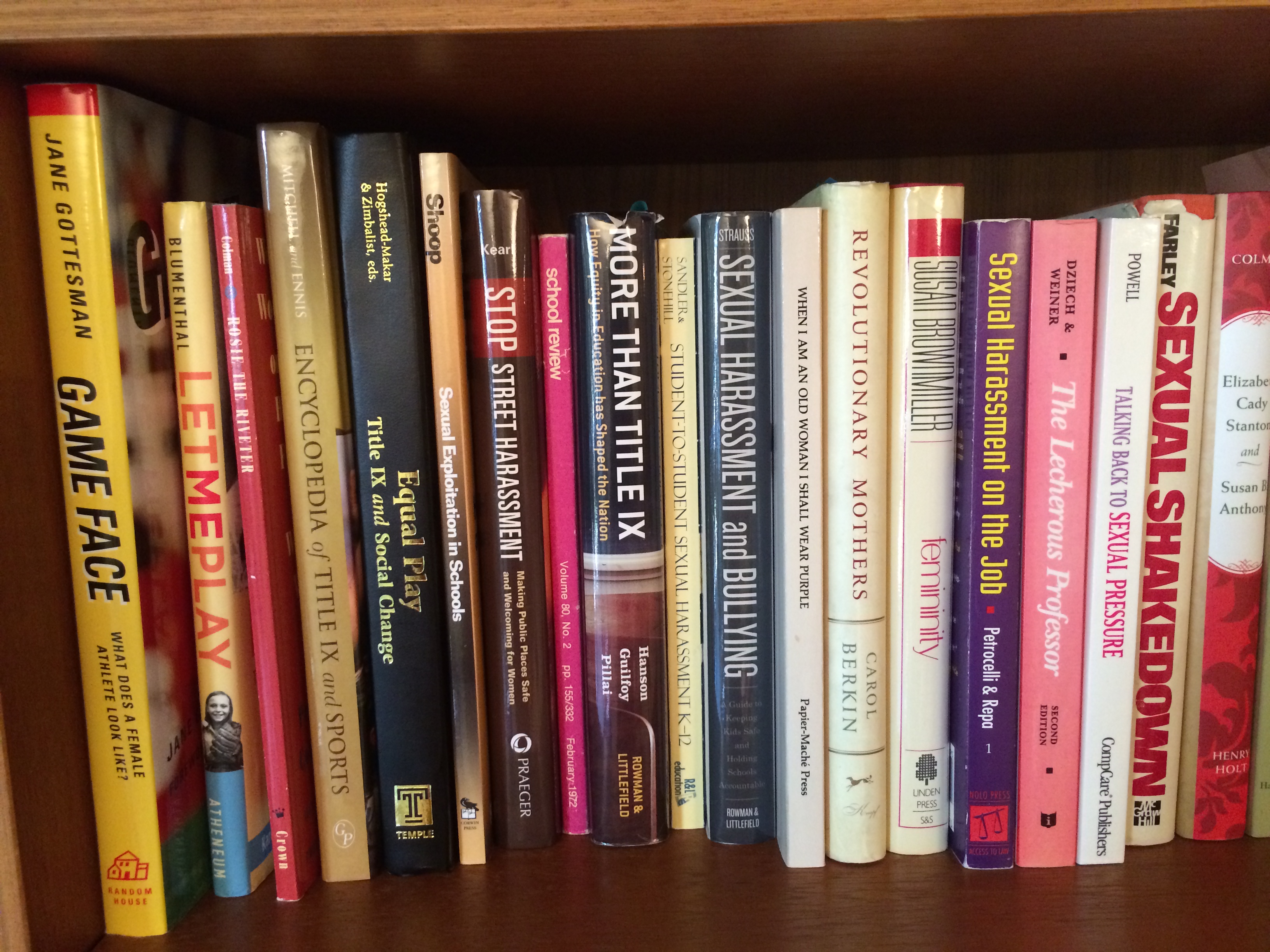

A graduate of Howard University, Gleaves had left a job at the Olivetti typewriter company to work for the Association of American Colleges. In 1971 the group hired Bernice Sandler to manage its new Project on the Status and Education of Women. Sandler hired Gleaves to work on the project with her, the first national project focused on promoting equity for women in academia, be they students, staff, or faculty. They helped Congressional staff develop and pass Title IX, and with subsequent recruits (such as Margaret Dunkle and Kay Meckes) produced some of the first reports on discrimination against women in colleges and universities, educated college administrators on their new responsibilities under Title IX, lobbied for appropriate regulations for Title IX, acted as a speakers and advisory bureau, and much more.

Often, in all these settings, Gleaves was the only African American in the room. She describes in the video what gave her strength in those moments.

I asked her if she thinks we’re in any danger of losing the gains made under Title IX. “Yes, there’s always a risk because there’s always fear,” she said. “In my opinion, discrimination, whether it be of race or sex, is based on somebody’s deep fear that they’re not going to get what they need, they’re not going to be who they think they should be, that somehow they’re going to be diminished because someone else isn’t.

“That fear is always going to be there to some extent. I think it’s in everyone, really. It’s just that you have to be strong enough to understand the fear is there and then move over it and beyond it and push it in the back, and say, ‘I’m going to be a human being. I’m going to be civilized. I’m going to be loving and gracious and do what the universe wants me to do, which is to treat everyone equally and make sure everybody has that opportunity to be a full human being.'”