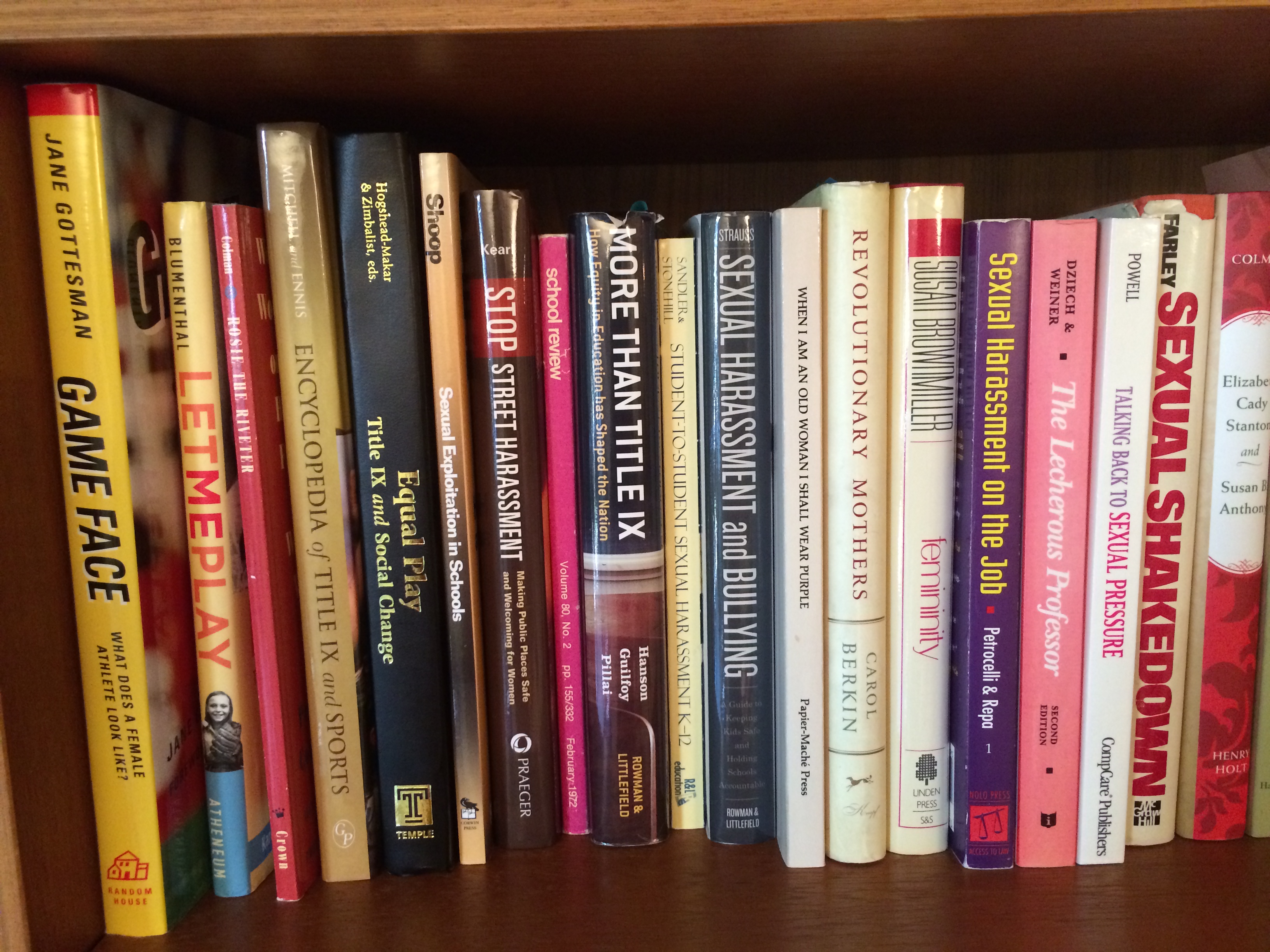

Title IX history coming out

(Courtesy Wikimedia Commons/philthecow)

Title IX turns 48 years old today. Part of its history is still in the closet.

People who face intersectional discrimination make up the bulk of movements against discrimination — in the grass roots, the grass tips, the leadership, you name it. I don’t know if there are statistics on that, but think about it. Women are more than half of people of color, of people with disabilities, of immigrants, etc. Some of the most visible leaders of the transgender rights movement have been trans women of color. Lesbians always played an outsized role not only in struggles against sex discrimination but in most other liberation movements.

In researching my book on Title IX history I’ve been struck by how often LGBTQ people appear in the story and how invisible they were, at least that part of them. Even today. Sometimes the invisibility was a political calculation; other times it was ignorance. I regret that I didn’t ask everyone I interviewed about Title IX to discuss their sexual orientation and gender identity in this context. But here are some tidbits through time, to give you a taste. And if you, dear reader, are someone I’ve interviewed and we haven’t talked about your Title IX experience as someone on the queer, trans, or non-binary spectrum, please contact me!

Via Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute,

Harvard University.

Lawyer Elizabeth (Betty) Boyer founded the Women’s Equity Action League (WEAL) in Cleveland, Ohio in 1968; WEAL became the activist home of Title IX “godmother” Bernice R. Sandler, the instrument through which Sandler filed federal complaints of sex discrimination against every college and university in the country. Sandler’s complaints via WEAL inspired Congressional hearings that led to Title IX. Boyer was rumored to be a lesbian. Sandler, who stayed in Boyer’s home on trips to Ohio, said Boyer lived with a woman (Maida E. Taylor) whose photo was on Boyer’s bedside table. Boyer founded WEAL as a way for women to get involved in the women’s movement who wanted to steer clear of the controversial issue of abortion. Nine years later she railed against WEAL embracing non-discrimination for lesbians, fearing it would alienate too many conservative members and stall movement momentum.

At the first Congressional hearings on sex discrimination in higher education in 1970 (inspired by Sandler), pioneering civil rights attorney Prof. Pauli Murray testified more than anyone about what’s now called intersectional discrimination. Murray’s experience as a Negro (her preferred term), a woman, a left-handed person, and the sole financial supporter of herself and elderly relatives taught her “the moral and social evil of locking this individual into a group stereotype.” A biography later argued convincingly that she was a transgender man in a female body. Murray never discussed this publicly.

The hotbed of homophobia in education was and is centered in athletics. As legal counsel for the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) in the 1970s, Margot Polivy proved invaluable in blocking attempts to destroy Title IX by coaches of men’s sports, especially football, and their Congressional allies. Polivy knew better than most the risks facing lesbian coaches who spoke out, being lesbian herself. But not once — even to this day — has she discussed her gayness with the other Title IX activists in the National Coalition for Women and Girls in Education, though she became close with some. Why not? Because “none of them asked,” she said. The Coalition met occasionally in the home she shared with her domestic and law practice partner, Katrina Renouf; at least some of them knew they were a couple. Polivy didn’t hide that. It just wasn’t talked about.

Via Yale AIDS Memorial Project website.

Five women students and one professor filed the first lawsuit about sexual harassment and assault under Title IX — Alexander v. Yale in 1977. It’s no coincidence that the professor was a gay man, Jack Winkler, who undoubtedly more viscerally felt the effects of discrimination than some of his colleagues. Alexander v. Yale established for the first time that Title IX prohibits sexual harassment in education. Some of the legal team at the New Haven Law Collective for the plaintiffs were lesbians. They continued to represent Pamela Price after a judge dismissed the other plaintiffs, reducing the suit to a “he-said, she-said” tort case pitting the word of a black woman against a white man. They lost the case but moved Title IX history forward

In the smaller cities and towns of America, stigma about sexual and gender orientation can be fiercer; the fear of exclusion for being out can be stronger. Over a 30+-year career in athletics administration and advocacy in Fresno, Calif., Diane Milutinovich has refused to answer publicly questions about whether she’s a lesbian. If she says yes, she figures, some people will dismiss what she says about Title IX. If she says no, it abandons others to lesbian bias. She can’t win, so she chooses ambiguity. But Milutinovich did win a $3.5 million settlement from California State University, Fresno in 1997 for sex discrimination and retaliation. She has helped other women there and across the country win tens of millions of dollars in legal cases under Title IX.

Many youths who felt freer to be who they are led the top Title IX battles of the past decade thanks to decades of activism by queers, transgender people, and women. Gavin Grimm, the most visible face of transgender students demanding their Title IX rights, is five years into a lawsuit that’s been to the Supreme Court and back and still going. In the movement against sexual violence, most of Know Your IX‘s early leadership was queer and about half were women of color, co-founder Alexandra Brodsky estimated in a 2018 interview. “I think that a huge amount of media attention has been on people who look like me and come from my school and all of that,” said Brodsky, a white Yale graduate. “But so much of the leadership has been women of color, has been queer women, that I don’t want us to buy into that narrative.”

The Academy Award-nominated film The Hunting Ground about the epidemic of sexual assault on campuses foregrounded the stories of Andrea Pino and Annie Clark, co-founders of End Rape on Campus. Pino’s biggest regret about the film is that it did not make evident how many of the assault survivors in the film and on campuses are queer, she said in a 2019 interview. That lack of visibility matters because the prevalence of sexual assault is higher against LGBT students than others. And as a Cuban American, Pino wonders, “What would it have meant if I was a visibly queer Latina in The Hunting Ground?” What would it have meant to some young Latina to see herself represented there? Visibility matters.

There’s a poetic justice to Title IX’s anniversary falling in LGBT Pride month. Let’s be proud of all of Title IX’s history.