Pawing through the papers of Title IX history

My “home” for two weeks of research: the Oregon Historical Society research library, Portland. (Photo by Sherry Boschert)

Here’s the thing about Title IX: Everybody I interview has a Title IX story. Some of the stories contradict each other. There are those that present clear pictures of the past, and others are a little blurry around the edges. Title IX is, after all, 45 years old — still young, but old enough for people to question their memories about it, or to question the memories of others. And old enough that some of the people involved in the beginning are, unfortunately, no longer with us.

Part of my job as a journalist and historian is to question the “facts” and opinions as they have been presented. Trust, but verify, as the Russian saying goes. The more I learned about Title IX, the easier it was for me to spot mistakes in some of the previous books about Title IX. I’ve conducted dozens of interviews seeking corroboration of certain story lines, tapping “primary sources” who speak from personal experience and were directly involved in Title IX history.

Everything from Congressional bills considered by Green’s subcommittee to correspondence with constituents and personal letters to friends gave me a sense of Rep. Green as a person and a politician, so she can come alive again in my book. (Photo by Sherry Boschert)

One of my favorite kinds of primary source material resides in research libraries. I’ve just returned from two weeks of exploring the voluminous papers of Rep. Edith Green (D-OR), the “mother” of Title IX, at the Oregon Historical Society, Portland, Ore. (A shout-out to the wonderful staff there — thanks for your help!) I pawed through 42 boxes of materials, barely a dent in the much larger collection she donated to the Society upon her retirement after 20 years in Congress but a lot to digest in so short a time.

It’s not glamorous work. Some boxes contained nothing helpful for my book. Others were so full of illuminating letters, memos, bills, and notes related to Title IX that I’d spend half a day working through one box alone. The rewards came from expected places (any folders related to the sex discrimination provisions considered by Green’s Subcommittee on Education of the House Committee on Education and Labor) and from unexpected places (like boxes full of “Controls,” which were tissue-paper carbon copies of every letter sent out from Green’s office).

The Edith Green and Wendell Wyatt Federal Building (with the slanted roof) stands on the Portland skyline as a testament to Rep. Green’s career. (Photo by Sherry Boschert)

I found things that I was looking for, like a step-by-step confirmation of how Title IX legislation developed, and Green’s reasons for finally voting against the bill that she’d fought so long and hard to create. (It passed anyway.) More fun, though, were the surprises. Like three letters from Ruth Bader Ginsberg, then a law professor at Rutgers University, offering opinions and assistance on the anti-discrimination measure. Or a personal letter to a friend and colleague in which Green talked about the final legislation that contained Title IX — the omnibus higher education amendments of 1972 — in more honest and forthright terms than she would allow herself to use in public. Then there were the exciting little finds, like memos showing how big a role Green’s subcommittee counsel, Harry Hogan, played in formulating Title IX, and how often he conferred with Bernice Sandler, Morag Simchak, and other characters in my book. Fortunately for me (and other historians), Green was something of a pack rat, and a very organized one at that. She kept originals and copies of nearly everything, it seems, and scrapbooks full of every news clipping that mentioned her. She also was wonderfully opinionated and not afraid to tell people what she really thinks. All of which made my job at the Oregon Historical Society library a lot easier.

Next stop, soon: Another stint of research at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Cambridge, Mass.

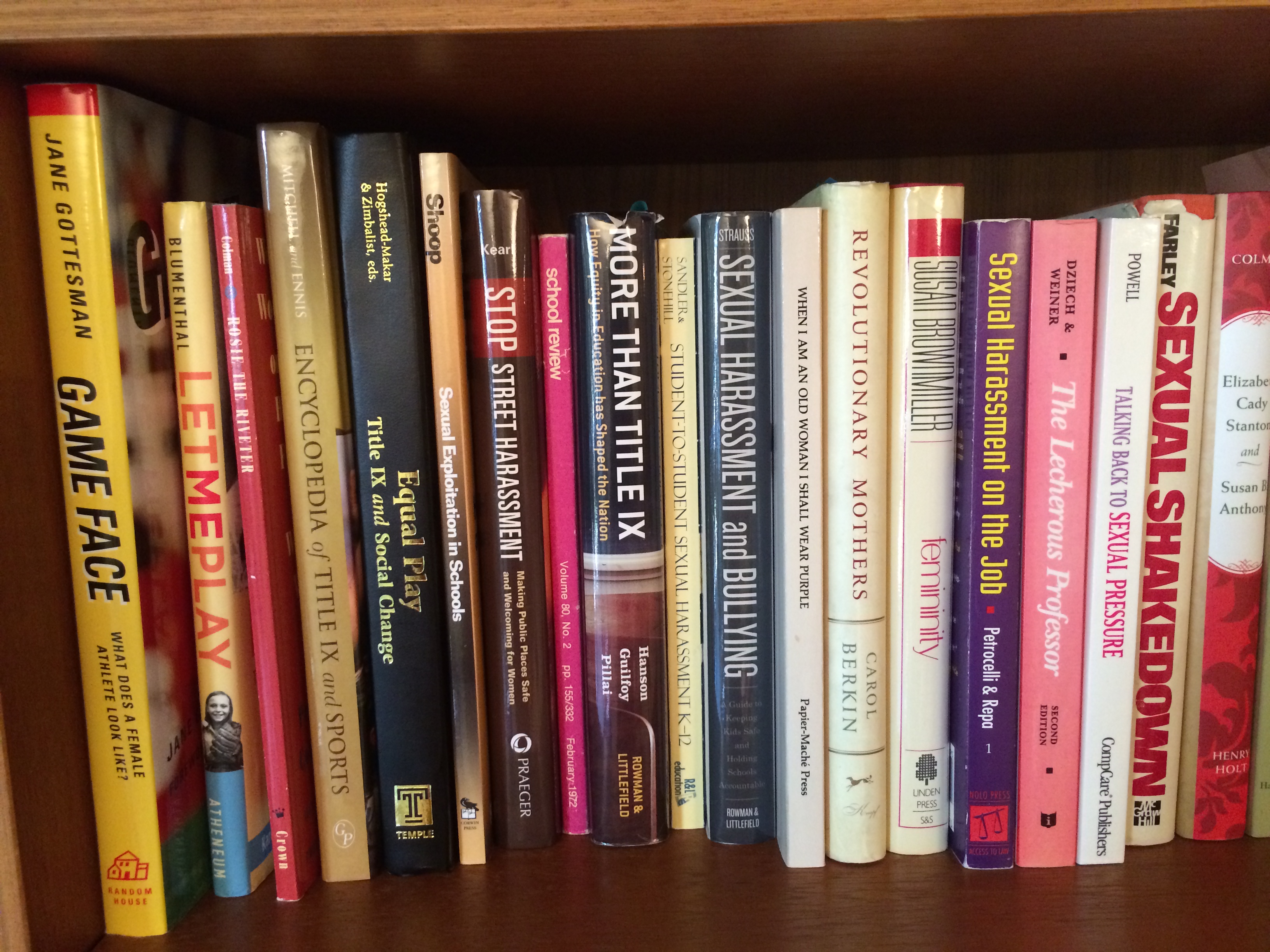

Now I’ll take some time to distill what I found in Green’s papers into the narrative of Title IX, converting the big picture and the juiciest details into prose to make the origins of Title IX come alive. Previously, I’ve done shorter stints of similar research at the Library of Congress and at the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Cambridge, Mass. I hope to return to the Schlesinger soon to dive deeper into its archives. Besides the papers of Sandler and the Women’s Equity Action League, they’ve got the records of the Project on Equal Education Rights (PEER) and its founder, Holly Knox, plus papers of the Project on the Status and Education of Women, which Sandler ran for decades, and much, much more. I’m considering trips to the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College, Northampton, Mass. and possibly to Indiana University, which houses the papers of Sen. Birch Bayh, the “father” of Title IX.

Sometime later this year, my archival research will be done. I’ll conduct more online research and further interviews, especially with more recent Title IX characters. I’ll concentrate on molding the manuscript into a lively narrative that makes readers want to know the story of Title IX, so they keep turning the page. For now, though, I’m enjoying the quiet coolness of research libraries, the smell of old papers, and the feel of tissue paper with ink that rubs off on my fingers.

Fascinating tidbits and pieces you put together Sherry. This is going to be an amazing book.