Hugh Hefner, pornography, and Title IX converge

One need look no farther than the obituaries for Playboy founder Hugh Hefner to see sexism still so firmly entrenched in our society. These came as I’ve been reading the latest book by Catharine MacKinnon. She’s a lawyer whose work was key to getting sexual harassment in education recognized as illegal under Title IX. Stay with me here — the two converge.

The print version of the Associated Press obituary for Hefner published in the San Francisco Chronicle today uncritically gushed about Hefner and his life. It parroted his self-assessed contributions to society and detailed his financial success and cultural influences. Funny, though — even though Playboy profited off the bodies and lives of thousands of women, and millions of women have criticized his magazine and the whole pornography industry for objectifying and demeaning them, the word “women” appeared only once in the version that greeted me at breakfast. Throughout, the reporter referred to “models” or “girls” or “waitresses” or “bunnies” (but without quotation marks). The only reference to women was, “Playboy ceased publishing images of naked women” in 2015 because they became so common on Internet pornography sites.

Missing was this paragraph that appeared in an online version of the AP obituary published shortly after midnight on Sept. 28:

“Other bunnies had traumatic experiences, with several alleging they had been raped by Hefner’s close friend Bill Cosby, who faced dozens of such allegations. Hefner issued a statement in late 2014 he `would never tolerate this behavior.’ But two years later, former bunny Chloe Goins sued Cosby and Hefner for sexual battery, gender violence and other charges over an alleged 2008 rape at the Playboy Mansion.”

By 2:30 pm, another online version of the obituary included more passages that didn’t make it into the Chronicle print version. (Excerpts in italics below.)

“Many feminist and [sic] regarded him as a glorified pornographer who degraded and objectified women with impunity. Women were warned from the first issue: `If you’re somebody’s sister, wife, or mother-in-law,’ the magazine declared, `and picked us up by mistake, please pass us along to the man in your life and get back to Ladies Home Companion.'”

I can’t for the life of me figure out why the Chronicle editors felt it was okay to gush about Hefner and pornography and exclude any female voice from the printed article. Oh, wait, I know — sexism!

“Feminist Gloria Steinem got hired in the early 1960s and turned her brief employment into an article for Show magazine that described the clubs as pleasure havens for men only. The bunnies, Steinem wrote, tended to be poorly educated, overworked and underpaid. Steinem regarded the magazine and clubs not as erotic, but `pornographic.’

“`I think Hefner himself wants to go down in history as a person of sophistication and glamour. But the last person I would want to go down in history as is Hugh Hefner,’ Steinem later said.”

Hefner and the courts that backed him maintained that pornography is protected by the First Amendment even though it causes harm. Following in their footsteps, alt-right fascists today claim First Amendment rights to spew hateful messages that incite violence and doxxing against anyone (especially women) who challenge them.

“Hefner liked to say he was untroubled by criticism, but in 1985 he suffered a mild stroke that he blamed on the book The Killing of the Unicorn: Dorothy Stratten 1960-1980, by filmmaker Peter Bogdanovich. Stratten was a Playmate killed by her husband, Paul Snider, who then killed himself. Bogdanovich, Stratten’s boyfriend at the time, wrote that Hefner helped bring about her murder and was unable to deal with `what he and his magazine do to women.'”

Hefner not only couldn’t deal with what he’d done to women. He pulled a common misogynist trick and tried to blame women for exactly what he’d done through pornography.

“`One of the unintended by-products of the women’s movement is the association of the erotic impulse with wanting to hurt somebody,'” [Hefner said].

Butterfly Politics

You might be thinking, What’s so wrong about pornography? What’s the big deal? It’s everywhere, so “people” must be okay with it, right? Sexism is entrenched in our society. It’s everywhere. That doesn’t make it okay.

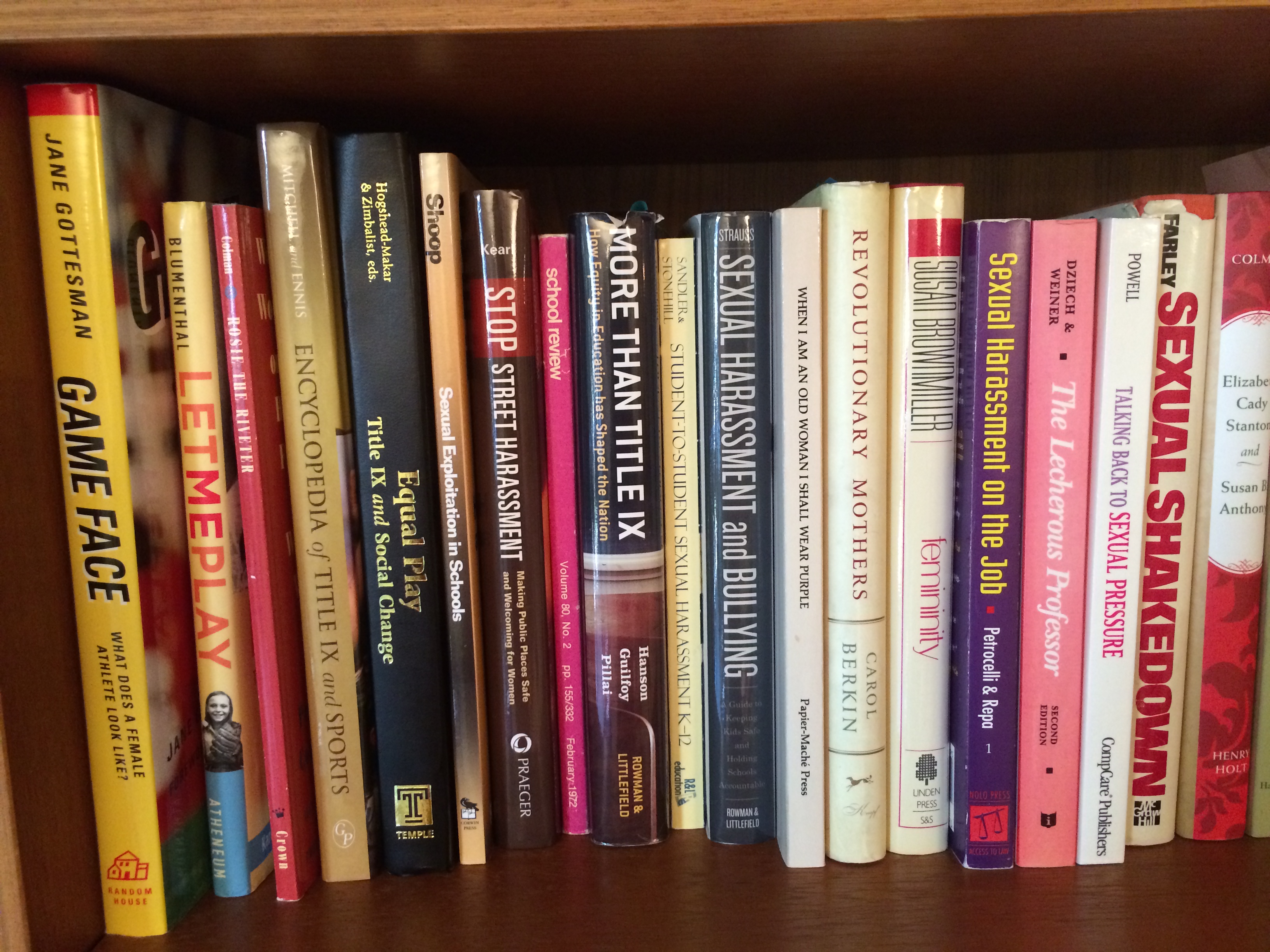

Catharine MacKinnon’s 2017 book Butterfly Politics presents talks she’s given over the past four decades, including on pornography. Some feminist ideas in the book took off and permeated society, and others haven’t yet. She makes the case for societal change analogous to the “butterfly effect” based on Konrad Lorenz’s 1972 mathematical models. A butterfly flapping its wings in the right place at the right time can set off a tornado thousands of miles away.

“Butterfly politics means the right small human intervention in an unstable political system can sooner or later have large complex reverberations,” MacKinnon writes.

“Butterfly politics means the right small human intervention in an unstable political system can sooner or later have large complex reverberations,” MacKinnon writes.

MacKinnon’s theories about law and sexual harassment informed the watershed Title IX case Alexander v. Yale, which established in the 1970s that the civil rights law known as Title IX should protect students from sexual harassment. No one today publicly supports the right of professors to demand sex from students in order to get a good grade.

For decades, MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin and others have been arguing that people should be able to sue pornography creators and distributors for civil rights violations, and win if they could show that they were harmed by it. Pornography “is integral to a sexist society in which the second-class status of women is sexually enjoyed,” she wrote in 1985.

The Hefner obituary describes him as a big supporter of civil rights. Clearly that support didn’t extend to women’s civil rights.

MacKinnon cites multiple studies showing that pornography does, indeed, harm. It increases the likelihood that someone with a proclivity toward abuse will be abusive. Pornography also harms the women you see in the photos. MacKinnon represented Linda Marchiano, better known as “Linda Lovelace,” featured in the 1970s pornographic hit movie “Deep Throat.” Marchiano was held captive, tortured, and brutalized into making pornography. Other pornography “stars” report similar treatment. Some get coerced into it in other ways, through financial desperation in a sexist society, indoctrination through sexual abuse in childhood, or other means. Under those conditions, saying someone “consented” to make pornography is meaningless.

Consent needs to be taken out of law’s treatment of pornography, sexual assault, and sex trafficking, MacKinnon long has argued. Let’s focus instead on coercion. “Sexual assault is a physical assault of a sexual nature based on coercion,” she said in a recent talk at the University of California, Berkeley’s Center for Law and Social Policy.

Which brings us to the current trend toward “affirmative consent” on college campuses. California law requires mutual consent as the standard for legal sexual contact on campuses. That concept is “groping in the right direction,” MacKinnon said. After all, “yes means yes” is a huge improvement over “no means yes.” But until we talk about the circumstances of coercion, we can’t understand why sometimes sex is an assault even if someone “consents.” Coercion can involve drugs, alcohol, abuse of power in a hierarchical society that systemically disadvantages women financially and politically, or sexist socialization, to name a few versions.

The current uproar under Title IX about sexual assaults on campuses is helping more people see that coercive sex is rape. Enough political butterflies are flapping their wings to help shift society’s definition of sex toward a healthier, mutually beneficial model.

Judging by the Hefner obituaries and the massively lucrative online pornography industry, we’re still waiting for the right butterfly flap to change the way we deal with pornography.